On Songwriting, Suffering, & Survival: The Practical Mysticism of Bill Mallonee (Interview, Part 2)

What’s it like to be regarded by critics as one of the “Greatest Living Songwriters” in the English speaking world, to produce 2 or 3 well-reviewed albums a year for two and a half decades, and to be looked up to by songwriters from Gospel, Country and general Americana traditions as a legend?

Well, for Bill Mallonee, it’s a saga of selling instruments to pay rent, of moving from a bustling music city to a remote mountain town for inspiration and thrift, of house shows instead of large clubs or stadiums, and of constant productivity. It’s a life of economic uncertainty, depression, a dubius future, and relative obscurity with mainstream audiences despite fame and respect among critics and performers in every genre he embodies. It’s also a life of artistic honesty, loyal friends and fans, and a hard-won yet isolating freedom that Mallonee has both chosen for himself and endured as a direct result of being the kind of “Built to Last” musician he feels driven to be in a culture that seems increasingly shortsighted and unable to savor anything but the flavor-of-the-month.

Over the past few months I have had the privilege of being on one end of a long and fascinating conversation with Mallonee. Like so many songwriters in “roots”, “folk” or “Americana” circles, I’ve been inspired by Bill’s music and life for years. I am also proud and fortunate to call him a friend. Mallonee has 75 albums to his name. After leading the successful alt-Americana band Vigilantes of Love for more than a decade under a fairly mainstream label, he embarked on a long and unusual new chapter as an independent solo artist praised for his songcraft–particularly his lyricism. He recently released a highly acclaimed new album, Slow Trauma, and over the past few months he’s been busy producing a new album for Muriah Rose, an extremely talented country folk singer who happens to be his musical partner and loving wife. And for the first time in two years, Bill and Muriah will be taking their songs on the road again, one house show at a time, starting sometime this summer.

Over the course of our pen-palling this year, I’ve been asking Bill about his take on just about anything I can think of concerning music, history, faith and politics in the US, and his personal reflections on how all of the above relate to the life he lives.

In Part 1 of our interview we talked mainly about the connections between faith, politics, and music in the modern US landscape, and Bill’s own journey in all that as a troubadour singing hard songs and sharing tough stories while trying to bring honor and offer hope to the working, struggling folks he meets on the road.

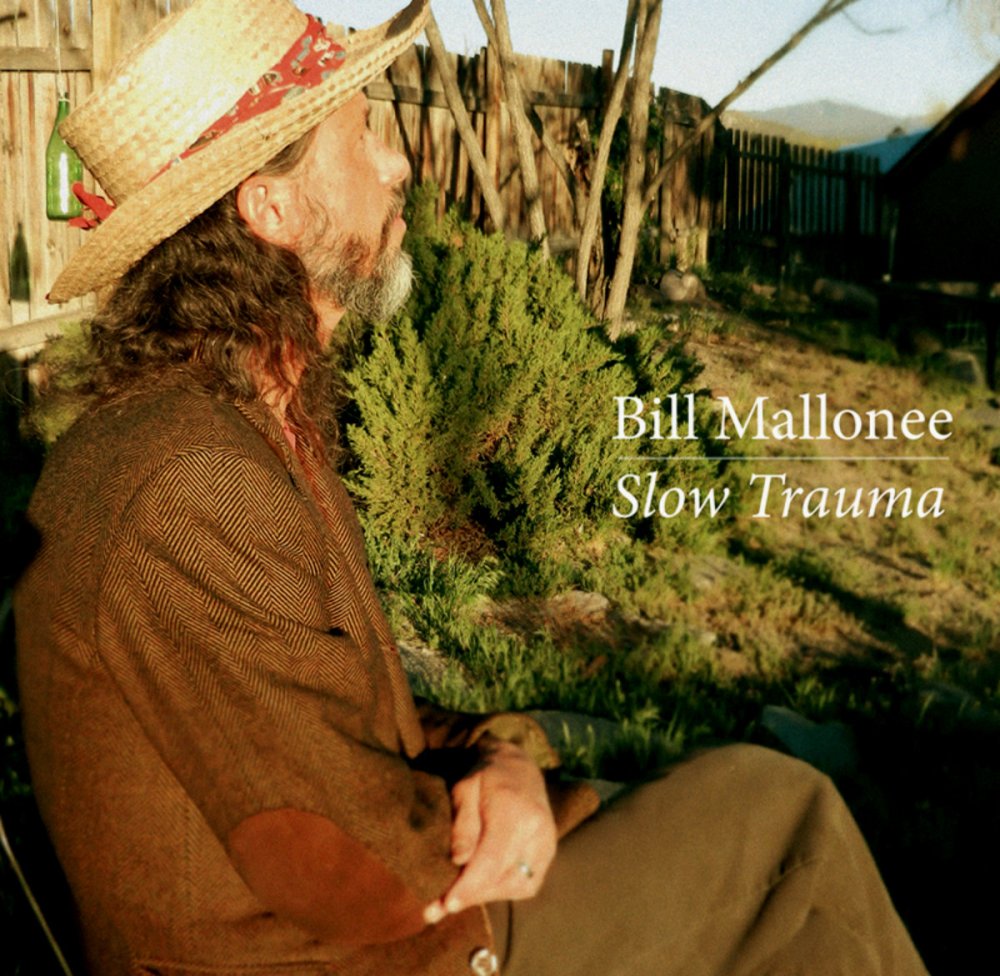

Mallonee’s latest album, Slow Trauma, 2016.

Mallonee’s latest album, Slow Trauma, 2016.

In Part 2, below, I asked Bill if he’d share more of his own insights into songwriting as a craft, how he does what he does, what it looks like to be an independent artist in the digital age, and how he processes suffering, his own legacy, and the future.

SM: Great to be talking with you again, Bill! Please feel free to go any direction you wish to with these questions. In this interview I’m hoping to hear your thoughts on songwriting as a craft-more specifically, what songwriting means to you, how you go about making songs, and what inspires you to do so. I’d also love to hear more about your relationship over the years with the “industry” side of music in the US, and your evolution from front-man in a successful band with a label to self-marketed, solo artist producing your own work and planning your own performances.

Let’s start with songwriting: how do you do it?

BM: Thank you. Well, I’ve always written about 50-75 songs a year. I started late in the game. Although I was a drummer for years, I didn’t pick up a guitar until I was 31. And I mean that’s when I was learning my first 3 chords. 7 years later, I had my first record deal, in 1991.

Being a songwriter is quest—a journey—on two fronts.

First, it’s a journey into the external world. You’re always attempting to improve your abilities on your instrument—to increase your knowledge of history and of the folks who excelled on the instrument. Who are the legends & virtuosos of your instrument? That would include the great records of the past, as well. It would include techniques, knowledge of gear and recording. All externalities.

But it is also a journey into an inner world. As a lyricist, I think that’s the most important aspect. Songwriting ought to be a journey within. I think that’s where the best songs live or are in the process of forming.

Anyway, early on, after Vigilantes of Love garnered the deal, I realized that “one record every year or two” was all labels wanted. That just wasn’t going to work for me. Too much to say and explore, and that leads me to the heart of your question.

Here’s the trick: You get to become excavator of your own soul and its perceptions. In the process you also become a conjurer, a healer, a shaman, preacher, jester and prophet.

It’s all Big Fun. Too much fun to be legal, really.

I sincerely believe that part of becoming a good songwriter just getting actively involved in that quest to find your own voice. After you learn a chord vocabulary and listen to some fav records it’s not really hard to write a song. What’s hard is writing a song that’s real. Something that’s got humanity, vulnerability and uniqueness oozing from it.

I think Nashville is full of paint-by-numbers type writers who can cough up a song in 10 minutes And get it heard on the radio. It all sounds a bit calculated to me. That’s cool for them. I’m glad for anybody’s success.

Honestly, it’s not my thing, although I think my work is very accessible.

But, writing a song that lays something vulnerable and true on the line, or a song that takes you to a different world, even if just for a few minutes? That’s a humbling endeavor. I think that’s harder to do.

And I think it’s harder to do because it involves “being” the song itself on some level. Your soul is invested in it. I’m not sure that’s something that can be taught or learned.

SM: Are you speaking about a kind of mysticism, then, Bill? A sort of “practical mysticism” that guides or drives your songwriting? Certainly you are talking about working with factors that go beyond technique.

BM: Well, I think it’s more like I was saying: It’s finding that voice and that subject matter that possesses your soul. And you get to be the one to conjure it and give it voice. A song is the making of a world that was veiled before you heard it. You, the songwriter/singer, get to reveal it and bring it to the light. Those are the songs that interest me.

That answer will tick some folks off.

SM: Why’s that?

BM: I’m sure that there are some folks out there who want the tidy formula and who write songs and have massive followings. For the most part, I have no interest in those kinda songs.

I’d say banish the tidy formulas, or at least hold them loosely. I admit the aesthetics I’m declaring here is taking us to the place where words leave off or are shaky, at best. But, that does not mean it’s “subjective.” To each their own. There is music that is heart-felt and from the soul, and other stuff that just kinda feels contrived.

SM: Has it always come natural to you, or is it a process that has gotten easier over time? And do you have a very set routine, or a personal regime to push yourself along?

BM: Song-making has been a journey like anything else. I am totally self-taught.

Drums were my first instrument and a stack of records kept me busy learning “how” they did it. Ringo, Charlie Watts. Later it was fellas like Ginger Baker & Cream, and Mitch Mitchell, Hendrix’s drummer.

I bet I wrote near 100 songs in 1985, the first year I really started taking writing seriously. Not saying they were great. I was learning on the fly. The songs themselves may have had much that was “derivative.” I was young at it.

But I will say the sheer exuberance of creating a song, its lyrics, its sonic textures, and then peopling it with characters who all had their own dreams, losses, motives and struggles was an overwhelming realization to me. And that initial exhilaration? It still feels that way to me whenever a song shows up. I love “chasing” all of it! Every aspect of writing a song and seeing it through to its fruition excites me. From the lyrics, to the chord progression, to the arrangement with the other instrument parts that will augment the song.

SM: Do you see yourself as more of a melody writer or a lyricist? Or is that a false distinction?

BM: I’m known, more or less, as a “lyric guy.” For me, a song has to reveal. A good song really is a lifting of the veil of our human condition. Ideally, it has to “birth” a feeling that wasn’t there before.

My songs still tend to have 4-5 verses instead of the “acceptable” 3 verses, though I have written as many as 10 verses for a single song on occasion. “Pristine”” off of the Permafrost album is a good example, as are many of the songs off my very first album, Jugular. We’re talking early Dylan-esque, the Blonde on Blonde through Blood on the Tracks era. But now I pare things down when I write the lyrics.

Jugular. 1991.

Jugular. 1991.

Permafrost. 2006.

Permafrost. 2006.

But back to the “routine” side of the equation. Yes, there is an element of discipline. There is editing and there are tricks to the trade. I seem to have to have a guitar in my hand when I write. I’ll keep journals and write lyrics from the passenger side on the road tours and then consult them later. But there’s no substitute for exploring with a guitar and seeing what shows up. Big fun!

Some of the themes in the books I mentioned in our last interview still serve to invigorate my way of seeing the world. Pablo Neruda (a poet), Maynard Dixon (a painter), Steinbeck & Kerouac (writers) are all inspiring to me personally and to my craft. At this stage, however, it’s mostly drawn from the “raw data” of my years and experience. Life and the people we meet and live among. What more do you need? A strange, sad, beautiful, broken world. And the stuff of good songs.

I just try and “keep my ears open and my nose to the ground” when exploring that world.

Sitting down with guitar in hand is like talking with an old friend, but one who is frequently still “revealing” something new about him or herself that I never knew before. It could be a new chord voicing, a new pattern of chords that suggests or unlocks a vibe or feeling deep within.

That’s really what writing is, for me anyway, in a nutshell: it’s a dialogue, a conversation going on between the guitar and the deepest parts of one’s own spirit.

So when I say a good writer finds his/her own voice, I think that really what’s going on.

You’re slipping into a stream of all that’s grand & good, broken & sad about this mysterious thing called Life and making it manifest for a moment. The stream is already there within you and around you. It’s the giving of voice and expression to those things the way you (and likely only you) can say it.

That’s why we should do all we can to tune into the songwriters of the past. That’s the eternal stuff. Their motivation and vision was not getting the cover of Rolling Stone or a write up in Pitchfork. Their hearts were truer and more unencumbered, I think. What I’m saying is there’s a vast differential between “Pre-pop culture world” and “Post-pop culture world.”

Circa (“field” recordings), 2007.

SM: Who are a few particular artists and lyricists that most inspire you as a songwriter—any folks you’ve taken cues from over the years while developing your craft?

BM: There are so many unsung heroes. The better known ones are far too many to mention, but I’m going somewhere with this: Robert Johnson, Ralph & Carter Stanley, Bill Monroe, Johnny Cash, Loretta Lynn, Tammy Wynette, Hank Williams, Jimmie Rodgers, Woody Guthrie; and think of all the incredible cowboy songsters like Gene Autry, Roy Rogers and Sons of the Pioneers. And folk artists like John Fahey and Leo Kottke. Far too many to name. Just incredibly gifted artists.

But here’s the kicker: to a person they were all formed in the crucible of poverty and deprivation. Loss and hardship. All of them immersed in a world of incongruities—of doubt & faith; of pain & joy; of win & lose; of do or die; of poverty & simple joys. Those were the raw ingredients of their lives and thus their songs. I want such authenticity in my work.

It was the deprivations and hardships they each endured that made their songs authentic. That place of loneliness and feeling forsaken. Those songs are still with us because they touch something universal. They sound like some ancient text from the lips of a beleaguered prophet. That’s beautiful work, the stuff that deals with the deeper issues.

I’ve also always been attracted to “modern” songwriters with strong character voices and very singular ways of doing what they do. They’re unique. Folks like Neil Young, Dylan, Jay Farrar, Leonard Cohen, Jeff Tweedy, Tom Waits, Mark Knopfler. And Mark Kozelek of Sun Kil Moon, the late-great Mark Linkous of Sparklehorse. All create worlds of lyric, mood and texture. All of them amazing to my ears.

SM: When is a song “finished” for you? Do you typically know or feel with some clarity that a song is complete? That it’s ready to share?

BM: Some songs “show up” almost fully formed. I think that’s a Spirit thing. At least it feels effortless, almost as if the song wrote itself. Those are the “in the moment” gifts. And they really are gifts.

It happens a lot for me, but I also attribute it to years of developing a sort of internal “knowing” how a particular song should go. You learn to trust your gut, so to speak. But it’s still rather mysterious to me and I am glad that’s the case.

I strive for a certain economy in the lyrics now. Usually, I’ll allow for no more than 4, maybe 5 verses. There’s a bit more editing going on these days. But, I honestly rarely second guess my lyrics. I will spend some time fitting the words into a cadence and vocal delivery that serves the song, but that’s about it. Ultimately, I think I’m striving for believability, for the authenticity that a good song should carry.

And over the last 8 years, since learning my way around a small home studio, I’ve also started to develop a particular “musical vocabulary” as to how a song should be augmented—how the guitars weave and interplay and speak with each other. As an arranger/producer, you realize that one instrument doesn’t have to bear the weight of the entire song.

That being said, for me it still all starts with a simple song, usually guitar centered.

SM: And what do you do with the stubborn songs—the ones that seem to have something golden in them, but they just never seem quite ready or finished? Do you have a safe full of those kinds of songs? Do you recycle them and use them for “parts-songs” when you’re building new melodies and writing new lyrics?

BM: Do I “recycle” on occasion, you ask? No.

Themes & concepts? Well, those are the things folks identify with you as an artist precisely because they hear certain things they relate to. Almost all genres have certain aspects that define them. Color too far outside the lines and it’s not that style of music any more, you know? I have my sounds, tones, voice and ways I approach a song.

My unfinished songs? Tom Waits once said in an interview that those songs of his that don’t get finished he dubs his “orphan songs.” He joked and said he’d send them out into the cold, unfinished, But they always seem to come around to the back door wanting admission. By that he meant that there was likely some aspect of those “orphan songs” that he eventually used or incorporated into some other song. I very much like that idea and have found it to be very true in my songwriting. It also means “write and keep writing!” Nothing is lost. Nothing is wasted.

Seriously: I try to not think too much about it. You listen “inside” first. That’s where the visceral organicity comes from, I think. You want that in a song. It’s gotta flow with a life of its own.

…and see? Now, we’re right back into the mystical.

**************************************************************************

SM: And staying alive? Without a label and agency of some sort to publicize you and your work, how do you survive financially?

BM: Well, it hasn’t been easy. My wife & I pretty much live in poverty. It’s very rough and uncertain. It’s been that way for 12 years now. Of course, there will never be “retirement.” Often, I’ve had to sell vintage amps and sometimes a guitar just to make the rent.

But, at the end of the day, sometimes a carpenter has to sell a hammer. Emotionally and spiritually, I guess you shake hands with poverty, keep doing what ya’ do, and let the chips fall. It’s been an historical given for so many great artists. Mozart, jazz artists Coltrane, Charlie Parker, and Thelonious Monk. Folk artist John Fahey. Again, too many to name. It was their vision and sound they followed first. The bank account was secondary. And that’s where I’m at after 75 albums over 24 years.

What to say? While I’d love a scrap of security, I’m not sure I’ll ever see it.

I try think this “life issue” through on a number of levels and make a certain peace with it, to tell the truth. Here’s as much as I’ve come up with:

FIRST, the “biz”, the “industry”, or whatever you want to call it today is set up for the short-view and the short-run. Longevity is out of the formula. No artists are developed anymore. That’s why there aren’t any new Dylans, aren’t any new Springsteens, or emerging Tom Pettys, or the next Neil Young.

Artists, if they’re lucky to be on a label, seem to get maybe 2-3 records and then their careers are over. Now, it seems, you come “ready made” with 50,000 fans in tow, or the powers that be take little to no notice.

Audible Sigh. 1999. From the VOL “label” days, produced by Buddy Miller, and featuring Emylou Harris.

SECOND, the music consumers of today don’t really listen to rock & roll the way they used to. It’s not “imbibed” anymore. I hung on the edge of my seat for the new Beatles or Byrds, the new Who album, Cream or Hendrix. I’d get on my Spyder bike and hit 5 miles to the K-Mart in Chapel Hill, NC (I was 14 at the time) to grab up the Lp of my favorite artist and digest all of it, the music, the album cover, the liner notes. I wanted to know what was going on in my musical heroes’ heads. How did they see the world? What made them happy? What did they celebrate? What did they disdain?

I don’t think “kids” listen that way anymore. A song is most likely a virtual backdrop to their virtual lives and their virtual integration into what’s cool as dictated by bought-and-paid-for media. There seems (to me anyway) a certain self-satisfied numbness that’s infected our kids today. Scary. And sad. Sad because their lives and their spirits are untapped. Our kids are so much more than what the media feeds them.

There’re some bright spots, though. For example, the resurgence of vinyl and the bands that make records on 8, 16, and 24 track tape machines is something of a Truth Quest for many young record buyers. I love that.

My old band, Vigilantes of Love, was on a major/minor label and had very consistent radio airplay from like 1994-1999. We lived in a van 180-200 days a year. That was our commitment to our art. But, incompetence and sluggishness ruled the day among the labels, managers and agents we were attached to. And yes, as it suggests, we did feel quite powerless. First you get sad, then you get angry. Healthy responses, I think.

End of the matter? You go back to the reason you picked up a guitar in the first place. For me it was never to master the business or to become rich and famous. It was to be a songwriter and a singer. It was simply to put the inside on the outside in the form of a song.

As far as the “purity” of my art goes, it’s great to be “indie” again. And, as you know, it means wearing many hats. Most of which have nothing to do with the art itself. It also means, at least for me, not being able to reach as many folks.

But I think perhaps the whole process has been a necessary winnowing. The “real” fans have hung on.

Spiritually, what does all this mean? Well, on the “bad days” one fights depression & bitterness. But, on the “good days” you celebrate the fact that you offered the world authentic “art from the heart” and made no compromises with a system that tends towards mediocrity and hipster-ism.

What does that mean in real practice, in the day-to-day? Well, it’s not easy. I just try to continue writing and recording honest, authentic, very personal music. It has to move me or I don’t release it.

Logistically, with no real entity (no manager, label or public relations) to profile and promote my records on a national level, I’ve had to re-think the wheel. What I mean by that is now I treat what I do as more of a cottage industry. Bring the cross-bar of expectations down a bit. That does not mean a lessening of quality. Artistic freedom means more quality. More grit, gravel, dust & diesel in the songs. More authenticity.

The “cottage industry” motif is not governed by the short view, or a hipster “flavor of the month” dynamic anymore.

Been there, done that.

There’s a great deal of liberation and satisfaction in doing what I do the way I do it.

It’s all driven by the greatest fans a fella could wish for. These are folks who still listen to music as if it mattered. To them, it does. This train is driven by my output of 2-4 new albums a year, and their enthusiasm and word-of-mouth. I’m very dependent on that handful of great fans to make the train run.

SM: Have you ever wanted to do something else—to completely change hats? If so, what are other” professions” or callings you’ve considered or felt drawn to? And why have you always stuck with music and songwriting? (For the record, I’m glad you have!)

BM: You know, I could have attempted to be a college professor. My love of American history & movements from, say, 1900 through the 60’s, might have been put to some use that way. Or perhaps a prose writer? I’d probably fail at both of them. So yeah, it had to be music.

SM: As an independent musician, Bill, you have worked extensively with numerous social media formats, such as bandcamp, billtunes, and facebook, to make your music available and to set up shows—as well as to make a living. Can you share a bit more of your thoughts on being an independent artist in the digital age? Has it gotten easier to “make it” as a musician without a label? If so, what does that mean today?

BM: Well the whole social media seems tired and weary now. It’s not new anymore. Everybody is on it. And here’s the one thing folks didn’t think about: much of the music and almost all of the presentation of digital media seems stricken with a soul-less-ness.

Why is that? Clearly there are talented artists “out there.” But, with a few exceptions, the work often strikes me as having a paint-by-numbers quality to it, like I mentioned earlier. Where’s the inspiration gone? Where are the new ideas? Social media just reinforces the notion that music is trivial, a commodity, some information to load into your device.

Lately, I’ve started to think the social media conduits were always over-rated. None of it has produced real community. None of it has produced longevity.

SM: Then do you think the old system—with huge labels—was better?

BM: The old superstructure had its bad, bad points. However, so many of those artists who were nurtured under the “old industry” are still here; still making great music. They’ve adapted, to be sure. But, there’s no denying that the old record industry super-structure sprung them and nurtured them first. Then, when all that comes from the internet did arrive, they had that to sustain them. Often, I see new flavor of the month indie artists breaking into the limelight from use of social media. But I don’t seem to hear about them 2 and 3 years later.

All the social media conduits are really a bit of a lie. Everyone is using them, so it really just makes it harder to be seen.

And the worst part? The worst part is the artist having to promote him or herself. I hate it. In a perfect world, we could just let the music speak for itself. The pond is quite over-stocked and past full. There’re a million “Americana artists” and new ones manifesting every month.

SM: That’s true. But, in a way, doesn’t this also mean it has gotten easier to “make it” as a musician without a label? Isn’t that the good side to all of this?

BM: What to say? Yes, in some ways it is easier now. But like I said, I think the gains we (as Vigilantes of Love) made early on were forged under the “old superstructure” of big label dynamics. Yes, we toured and worked our tails off. We delivered great sets under all conditions every night. And there was enough of a “new-ness” to the whole indie music thing that it was embraced by radio, MTV and a goodly number of folks. So, we made fans that are still there.

But now? Nothing’s really “new and amazing” anymore. That’s what happened after the digital chip, MP3s and social media made everyone a star. When anyone can do it, everything’s reduced to triviality. As far as the recording standards go, I’m glad folks are pushing back against it. Like Neil Young, for example, with his Pono music venture. You buy the player and get superbly mixed and mastered recordings at higher bit-rate levels. I don’t own one, but I’ve heard lots of folks say they love what they hear.

And, I’m sorry this sounds harsh, but it really needs to be said. While the social media conduits have been a boon to many indie artists in getting their name & music out there, it’s also that same social media system that has tended to “legitimatize” everyone. Now every wannabe and hack is just as “legit” as anyone else. Nothing wrong with that at all. It’s a capitalist democracy. Sure, put your stuff in market place, whether you have anything to say or not. In my opinion, it’s just makes for a lot to wade through.

SM: The “bard” is an oft-romanticized but even more often misunderstood character in society. In your opinion, what are a few of the biggest misconceptions you face when it comes to people’s perceptions of you and your music? If you could set the record straight for folks who are curious about the life and work of an independent musician today in the US, what are few things you would share?

BM: Well, I’ve answered much of that already. I think folks in the US and in most western countries over the last 30 years have come to think of music as merely a “commodity”: something to be consumed, a mere “adornment” on their lives. That’s what happens when there’s too much of anything. It becomes trivialized.

Listeners these days also tend to think that somehow music just magically appears and should be free or close to it. I really don’t think that’s the way “real” songs work. Like I said above, there’s tons of rubbish out there. It being free doesn’t make it any less rubbish.

About myself, I would just tell folks:

Look, what I do as an artist isn’t for everybody. But then again, there is no one music that is. What I strive for in my work is an authenticity; an authenticity that’s not ‘borrowed’ or ‘mimicked’. It’s been born out of hard work, poverty, deprivation and more hard work. It’s been a dogged (and joyful) following of my own muse. If that’s the kind of music you like then I have plenty of it. And yes, it’ll cost you something. Nothing extravagant. But something.

I make each of the 75 records I’ve made available at a fair price, usually way less than a dollar a song, if one buys the whole album. But I take this seriously. There’s a “worker is worth the wage” theology embedded in how I do what I do. No shame in telling folks that if they want the “good stuff” they should be willing to pay something for it.

SM: What does supporting an artist look like for you? What are the best ways that fans of your music can support you and the work that you do?

BM: Supporting an artist is, when it’s all pared down, really just a form a nurturing. It can also be a form of community. You see, it’s bigger than just the music. It’s Life, and we’re all in this together on the same planet.

You can never go wrong with good folks staying in touch. I have a fan-base comprised of some folks who’ve been there for over 20 years. That’s no small feat, in my book. We did it through relentless touring and releasing new albums every 6 to 9 months. To be able to garner folks’ initial interest and then have them follow you through your artistic journey is very flattering. And very nurturing.

My fans, although few, are usually pretty good about buying the records, booking shows for us (I usually prefer the house shows like you & I have done in the past!) and then spreading the news by good-old-fashion-word-o’-mouth.

SM: Bill, your songs often touch on deeply political or religious themes, particularly the daily struggles of those without power to survive in contexts where there seems to be little hope or comfort. However, I have rarely heard you described as either a political singer or an overtly religious artist. What is your take on this? Do you see yourself as doing political or religious work? What are your thoughts on the relationship between art and politics and religion? These days in particular?

BM: Fabulous questions!

First off, if that’s the “take”, the perception on who I am and “how” I do what I do, then I’m happy. I don’t want to be seen as a religious artist because in my estimation we’re all religious whether we’re tuned into that or not. And I don’t want to be seen as a political artist either. So many religious and political stances start with the artist pontificating from some higher moral ground, from some place of judgement. It’s all a bore or propaganda or both.

For me, I think it’s best to loosen up one’s preconceptions about how a song will turn out. Go at it with fewer foregone conclusions about how one feels and thinks about the “bigger things” in order to write a more honest song.

That does not mean those songs won’t be suffused with one’s own views of Faith, Hope and how Love should manifest itself in the world. But to me, it suggests at least 2 things.

One, it means that you the artist also have the courage to speak of what it all looks like on the “bad days” as well as the “good days”. And two, it also means that whatever your perspective is, it’s not your “agenda” when you step up to the microphone or into the recording studio. It’s really just an extension of immersing oneself in ragged and hallowed humanity and talking about its dreams, its hopes, its sadness and its griefs.

SM: What advice would you give a new artist who feels dead set on pursuing music as their life’s calling? Are there general starting points, or “essentials”, that you would hope for them to consider and pursue?

BM: I think some of these have been addressed already, but I would just add a bit of a “pep-talk.”

Learn your instrument. Learn as many as you’re able. Play “live” when you’re able. Performing is a great teacher. Read music and artists’ biographies; understand what gave them their vision and what they were up against in their own days. Read history, especially that of your own country. And listen to everything you can. Cross cultures and listen to the traditional musics of other countries. It’s amazing. You realize that you are not alone. And you will find the vestiges of their genius everywhere. Such “immersion” will make your heart bigger. And such knowledge will keep you humble.

And the home front: family first, always family first. No marriage or family is worth busting up over one’s “big chance” or “big career.” All that stuff is illusion. The real is always human, always hallowed, always the priority.

SM: After getting married, you relocated. How has life with Muriah–living together in New Mexico– influenced what you’re doing and thinking these days?

BM: New Mexico is beautiful, almost other-wordly in terms of its topography and the character of the land. It has something that makes one’s heart bigger, it seems to me. Many a visual artist has been coming here for 100 years because the light has a quality that is not found anywhere else in the US. I came for the land, the people, the climate, the inspiration—and the low rent. But NM is also very undeveloped in many ways. It’s a poor state with poor state problems. Unemployment and lack of education opportunities keep it as a kick-dog state.

We’re dirt poor. Muriah and I toured heavily the first 8 years of our marriage. It was grueling. I was still writing and releasing 2-3 albums a year during that time. We took the last two years off to just get some perspective. During that time I think I made 8 albums to get us by, including a Christmas album. But even then I had to sell some of the little gear I have left to make ends meet. Amps, guitars, stuff I thought I’d have forever. It’s all part of the ritual now.

We fight a big battle with depression over what seems like diminishing options. I’d like to produce more artists. I have a modest recording rig and lots of experience. I can get you that “Bill Mallonee” sound (laughs)! But, for the most part, I think folks are saving the money & making records in their own garages and basements these days.

SM: Do you feel hopeful about the future? Your future? The future of the American people? The world?

BM: I’ve never felt “hopeful” about my future. You make a certain, uneasy peace with the uncertainty and poverty and just go from there. I don’t think the Lord guaranteed anything here except His nearness. And I think His near-ness and grace is enough.

Professionally? Short of “being discovered” or finding someone to put the music in front of some shakers & movers, I suspect I’ll being living under a bridge somewhere eventually.

I wish it were different, but if anything great is going to happen for my work, I suspect I’ll have to die first. Even then, it’ll probably be seen as a fool’s errand.

But, like I said, I stand by the art. All of it. Every song. Every album. Every word. For all of the lack of resources I’ve had to record and preserve it, I’d put the work up against anyone’s.

America? We’re amusing ourselves to death. Numbing ourselves with devices and big pharma drugs. Our souls are drying up. Technology has emasculated us in many ways. We make almost nothing here now. And yet we have the brightest youth in the world. Gifted beyond measure. The best minds. And we’d solve many a-problem if we’d let them have the initiative again. Gotta let the horse run. What happened to good old American Ingenuity? Used to be, we could solve any problem. Corporate America came in & stole that initiative from the fella who could “build the better mouse trap.” Now where’s clean energy? Where’s the electric car, for example? Where are the jobs that give dignity and by which a man or woman could provide their families with a better life?

Who stole that dream? Who killed our imaginations? And why? How did the noble concepts of the “common man” and the “middle class” disappear? Why are we seen as, and encouraged to be, nothing more than consumers?

A sense of despair and hopeless-ness was the theme of last year’s album Lands & Peoples. It named names and attempted to hold a mirror up to our spirits. We might be living in the new Dark Ages. We’re an oligarchy, a plutocracy. Hard Times. Sure, there’re a few voices of dissent, a few prophetic voices. But for the most part no one’s really blowing the whistle on any of it.

Lands & Peoples.

You reap what you sow. We’re sowing the fruits of illiteracy, ignorance & fear. We are a people polarized by religion and politics. And thus we’re easy prey. Corporations are the least “patriotic” entities on the planet. Jobs vanish, sent overseas. “Bigger is best” and “too big to fail” are the mantras taken up by our media-hungry politicians. Thus, “big” everything dominates our lives. Big Agriculture, Big Coal, Big Oil, Big War Machine, Big Pharma.

Education seems to be reduced to “what I have to do so I can get a job.” And even that’s no guarantee. The notion of learning and studying to greater love humanity and then render some help to our most pressing problems is out the door. It seems like “the 1%” insulate themselves from what appears to me to be cultural breakdown. It’s a failure of leadership. They lack integrity and we’re not calling them out on it.

Hey, when you’ve got states like Texas ruling against individual counties even voting on banning fracking, then you know there’s some serious bought-and-paid-for politicians.

Charlatans and weasels. I don’t think that’s an isolated incident. Such corporate domination is playing out in many areas.

At the end of the day? For me I try to be about the things I can control. I try to write a better song today than I did yesterday.

I try to be a loving and real human being. I’ve got my hands full.

I suppose one can only really keep one’s own parcel of life in order. And even that’s a stretch for most folks, I know (Lord help us!).

~ bill mallonee

*******************************************************************************

To learn more about how you can support Bill Mallonee and his music, go to the “Community” page on his bandcamp website (https://billmalloneemusic.bandcamp.com/ ).

Also, Bill and Muriah are currently making plans to tour again, all across the US, and they are focusing on house concert venues. If you or someone you know is interested in hosting a show, contact Bill at : highhorsebooking@hotmail.com.

*All pictures taken from Bill Mallonee’s bandcamp page.